Friday, May 22, 2009

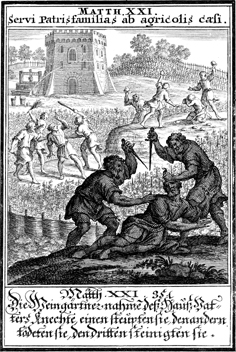

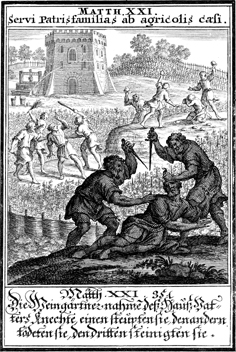

The Parable of the Wicked Tenants

This rejected stone will become a stumbling block, as stated in Isaiah:

Friday, May 15, 2009

Is Buddhism another form of Hinduism?

Is Buddhism another form of Hinduism?

Buddhism in it’s purest form is in many ways the most minimalist of religions. Therevadan Buddhism has been called both the most and least mystical of all religions. It has been regarded as both the most spiritual of religions, and not a religion at all.[1] In many ways, it is religion stripped to its bare essentials.[2] Hinduism has long been regarded as being syncrestic, and almost spongelike in its ability to absorb any form of belief [3], so it may be assumed that Therevadan Buddhism would be able to be regarded as another form of it. This observation is made even stronger when we look at both religions’ higher, mystical aspects, in particular, their views on the self, and time. It is however the opposing views on God, or a transcendent being that turn any such similarity into an uncrossable bridge. As Hindu mystic Kabir states:

“the difference among faiths is only one in names;

everywhere the yearning is for the same god”[4]

The difference between Hinduism and Therevadan Buddhism is that the latter does not yearn at all for such a being.

Indian religion has always been hospitable, absorbent and syncretistic. The religious beliefs of different schools of Hindu thought vary, their practices differ greatly. Within Hinduism there can exist many types of belief: monism, dualism, monotheism, polytheism, and pantheism.[5] However, within this there is one constant: a belief in a transcendent being, a God.

A Theravadan Buddhist does not believe in a creator or absolute being at all.[6] Therevadan Buddhism offers salvation that does not involve belief in God, or a belief in an afterlife. Buddha deliberately did not speak about a creator of world. Instead, he offered the concept of becoming an arhat, one who has achieved nirvana: absolute extinction of the mind and total cessation of all sorrow and suffering.[7] Within this is a blissful state, akin to “the extinction of a flame” there is no sorrow, yet no happiness.[8] Nirvana is contentless, it is not to be regarded as a creator, nor is it spoken of as an underlying reality. It is referred to as Uncreated, Unbegotten, Immortal.[9]

While Therevadan Buddhism contemplates that there is no simple pure substance which is permanent or has it’s own individual substantial existence, the great nothingness,[10] Hinduism thinks the basic substance of the universe is spirit. The reality behind all and every phenomenon is spirit: everything lives in spirit; it is the seed from which everything comes.[11] Ultimately, there is nothing in the universe that is not God.

The pertinent difference between Hinduism and Therevada Buddhism may be summed up in two quotes that concern the self’s relation to reality: “This is not I” and “thou art that”.

The Buddha would often state “This is not I” when referring to physical or conditioned reality, as opposed to dharma, absolute reality. By reaching nirvana, he has transcended the aeons, he is atemporal and timeless.

There is neither past nor future, all times are present [12]

This is expressed differently in Hinduism. The fundamental Hindu assertion is “thou art that”: the atman, the individual self of man, is identical with Brahman, the universal self.[13] Within man dwells a greater self, the Atman. Man is the house of spirit. The soul of man is the same as God: immortal and unchanging, pure divine light. “The knowledge that Brahman and Atman are one and the same is true knowledge.”[14] Man does not see the world and himself as they truly are, he has been deceived by the appearance of the world, which conceals the true reality. The self that he thinks he knows is not the true self.[15] The man who has entered into this mystical state has thrown off the illusion of ego, and realised his greater self.[16]

In reaction to this emphasis, the denial of atman is a central Buddhist doctrine.[17] The atman is replaced by the anatman, or no-self.[18] While both regard the absolute extinction of the mind as central themes,[19] the main distinction is that within Hinduism, it is in reality more of a transformation or transmutation of self. This is regarded as deification, or union with God.[20] The self is completely absorbed into the divine, whereas in Therevada Buddhism the self is completely annihilated.

The main concern of Therevadan Buddhism is to find both the reason and remedy for one’s own suffering, which comes from being born. Man is bound without and within by the entanglement of his desires.[21] The object is to go from life as one knows it , samsara, to nirvana, life as it actually is.[22] Nirvana is an absolute reality, inconceivable to man in his present state. The finite mind of this state can never know the infinite of nirvana;[23] Nirvana simply is. It cannot be conceived, only experienced[24]. As in Hinduism, the difference between this transcendent state and the mundane, between complete liberation and the ordinary is emphasised.[25]

Within Hinduism the true object of man is to be annihilated into the Spirit, to escape bonds of historical succession. The meaning of existence is not found in history, the whole goal of creation is found to exist outside history.[26]This deliverance is achieved by imitation of Brahman. As the human condition is defined by opposites, liberation from the human condition is equivalent to a non conditioned state in which the opposites coincide. The enlightened Hindu remembers with horror the state and the world of ignorance where he was before.[27] For him who knows, time and timeless lose their tension as opposites. The manifest and unmanifest aspects of being are no longer distinct from each other. [28] Within Brahman, emptiness and fullness are one.[29]

In both Therevadan Buddhist and Hindu mystical speculation, time is thought of as unlimited. However, the two regard this in differing ways. To the Therevadan Buddhist, one of the goals of life is to escape time. To do this, one needs to abolish the human conditions of desires and suffering by attaining nirvana. In Hinduism existence in time is ontologically a non existence, an unreality.[30] The physical world is illusory because it lacks reality; it lacks reality precisely because it is of limited duration.[31] It is the very fluidity of time that conceals the fact that it is unreal[32]

In both Therevadan Buddhism and Hinduism, there exists a realm that exists outside of time. [33] In Therevadan Buddhism this is thought of as being an eternal present; stasis; a non-duration.[34] The Hindu concept of Brahman as containing all polarities and opposites in one being explains this as time and eternity as being two aspects of the same principle.[35] In the Upanishads, Brahman is conceived of as both transcending time and as the source and foundation of all that manifests itself within time.[36]

While there is much that would suggest that Buddhism may in fact be another form of Buddhism, it is very difficult to conceive of a nontheistic faith as being another form within a family of faiths, that, while varied and comprehensive, are all theistic. It may best be illustrated by using the following quote by the Hindu mystic Dadu:

Who can know you, o invisible, unapproachable unfathomable? Dadu has no desire to know; he is satisfied to remain enraptured with all this beauty of yours, and to rejoice in it with you.[37]

A Therevadan Buddhist would not say such a thing. The very fact that it is addressed to a transcendent being, no matter how “invisible, unapproachable unfathomable”

The Hindu mystic Rajjab stated “The worship of different sects which are like so many small streams, move together to meet God, who is like the ocean.”[38] By using this thought, it is improbable that Buddhism could be another form of Hinduism. Indeed, it may even be a stream, yet not one drop of its water would know of the ocean’s existence.

Dasgupta, S.N.; Hindu Mysticism (1983) Motilal:

Eliade, Mircea; Images and Symbols. Studies in Religious Symbolism (1961) Harvill Press:

Happold, F.C.; Mysticism. A Study and an Anthology (1970) Penguin: Middlesex

Hopkins, Jeffrey; Meditation on Emptiness (1983) Wisdom Publications:

Humphreys, Christmas; Buddhism (1958) Penguin: Middlesex

Johnston, William; The Still Point (1982)

Kakar, Sudhir; The Analyst and the Mystic (1991) Viking:

Katz, Steven T.(ed); Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis (1978) Sheldon Press:

Otto, Rudolf; Mysticism East and West (1960) MacMillan:

Sen, K.M.; Hinduism (1978) Penguin: Middlesex

Sinnett, A.P.; Esoteric Buddhism (1888) Chapham and Hall:

Sircar, Mahendranath; Hindu Mysticism According to the Upanishads (1974) Oriental Reprint:

Smart, Ninian; World Religions: A Dialogue (1960) Penguin: Middlesex