Here is another essay that has been causing me grief.

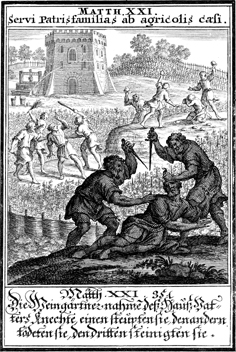

Jesus teaching with Parables consists of using the unknown with known, the strange with familiar.[1] The parable of the Wicked Husbandmen is unique among the parables of Jesus due to it essentially being an allegory. Here the vineyard is Israel

In Isaiah 5:7 the House of Israel Israel

At this time in Palestine and Galilee , many landowners were absentees.[5] This gives the parable a sense of reality, as there was unrest due to landlords living elsewhere[6] Luke adds to this “for a long time,” to emphasize the amount of responsibilty given to the tenants, to state they were trusted.[7] It is the owner’s absence rather than his departure that is illustrated in the parable. The God of Israel is being represented as an absentee landlord. [8] The absence represents the distance between God and the religious leaders of the time, due to their own withdrawal.[9] His absence is in actuality theirs. He had not forgotten them; he will send his slaves, and his only son.[10]

In Mark and Luke, the slaves are sent “in season”. Due to the winepress being mentioned, this would be the time of winemaking, not the actual harvest as is stated in Matthew.[11] Either way the slaves are sent at appropriate times in history of salvation.[12] The sending of slaves refers to the sending of prophets.[13] The slaves are arranged and treated differently in each version. In Matthew, the slaves are sent in two groups; this may represent the former and latter prophets.[14] In Mark they are sent as individuals to portray the distinctive message of each prophet.[15] In Luke a single slave is sent each time, the violence each time escalating, climaxing in the killing of son.[16] Whether the next messengers are sent in the same season or the next is not stated, but the central point is that the trouble does not start straight away. Not only are the husbandmen given several opportunities to pay their rent, the message to do so is delivered in differing ways by different people.[17]

By using the same nomenclature as was used at both Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration, “beloved son” alludes to a christological interest.[18] The sending of the son is not only theological; it follows the logic of the story.[19] The owner expects his son will be well received. The arrival of son allows the tenants to think the owner has died.[20] Earlier it had been just slaves who had been sent who had no personal interest in estate. The one and only son is sharply contrasted with many slaves.

This is stated elsewhere in the New Testament:[21]

Long ago God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed heir of all things.

Hebrews 1:1-2 (NRSV)

The owner represents God by showing mercy and being long suffering.[22] By pursuing the contractual arrangements to end, he shows Gods fidelity.[23]

In Matthew and Luke, the son is thrown outside, and then killed.[24] This is similar to the Passion story in Matthew, where Jesus is crucified outside the city.[25] This analogy is awkward, as the vineyard represents Israel , not Jerusalem

To understand parable it is essential that the owner is living away. By removing the sole heir, the tenants can take unhindered possession. The law states that under specific circumstances an inheritance may be regarded as ownerless property, which may be claimed by any one, with the proviso that the priority right belongs to the claimant who comes first. [28]

At this point in the parable, Jesus uses a quote from Psalm 118. Jesus’ view of the Old Testament was very spiritual, he felt it transcended his own age. He would have seen in Psalm 118 not a direct reference to himself, but only “the statement of a principle applicable to himself.” [29]

Psalm 118 was one of the primitive church’s proof texts for the resurrection and exaltation of rejection of Christ.[30] The whole of psalm 118 is a vindication of Gods purpose. This final week of Jesus’ earthly ministry is to be seen in the light of Gods victory snatched from defeat, God’s selection of his own people, and the new Kingdom of God, in gathering of the elect into Father.

The cornerstone referred to is the head of the corner, the stone used in buildings corner to bear stress and weight of the two walls; it is crucial to whole structure. It is this elevation of rejected stone into its predestined place at the head of the corner in which the Psalmist see the hand of God.[31]

This rejected stone will become a stumbling block, as stated in Isaiah:

He will become a sanctuary, a stone one strikes against; for both houses of Israel he will become a rock one stumbles over—a trap and a snare for the inhabitants of Jerusalem

Isaiah 8:14-15 NRSV

The stone of offence is God, a refuge and sanctuary to those who trust in Him, a snare to the faithless. This speaks of the refusal of Israel

A chief cornerstone would not be likely to trip or fall on a person.[33] Christ will be a stumbling block for some, and they will suffer heavily for their shortsightedness.

In between the quote from Psalm 118, and the clear reference to Isaiah 8:14-15, Matthew adds the following:

Therefore I tell you,

the kingdom of God

will be taken away from you

and given to a people

that produces the fruits of the kingdom.

Matthew 21:43 NRSV

In Matthew alone is the Vineyard referred to as the kingdom of God

Because the rulers will kill the Messiah, the vineyard, the Kingdom of God Israel Israel

While the parable of the Wicked Husbandmen may be a very lofty allegory, it is its realism that makes it so tangible. It is a resemblance to a social reality. First, it has a strong resemblance to social reality. The fact that there was unrest in Palestine and Galilee due to landlords living elsewhere,[39] starts the parable off in a realist way. Another element Jesus audience would have understood was that the “payment in kind” which the tenants were to pay the landowner had led to many disputes with dishonest tenants who had leases.[40] None of this is really unusual for Jesus’ teaching; he was always vindicating the poor, the despised and alienated. Here the tenants have opposed and rebelled against God. The rulers will be dispossessed. They will not only lose the blessing offered, but what they reject will actually cause their overthrow.

Bibliography

Albright, W.F.; Matthew (1986) Doubleday: New York

Allen, Willoughby C.; A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Matthew (19??) Edinburgh

Creed, J.M.; The Gospel according to St. Luke (1930) MacMillan: London

Dodd, C.H.; The Parables of the Kingdom (1961) Fontana : London

Dormanday, Richard; “Hebrews 1:1-2 and the parable of the wicked husbandmen” in The Expository Times (Vol 100. No. 10; July 1989) pp. 371-375

Fitzmyer, Joseph A.; Luke (1985) Doubleday: New York

Gould, Ezra P.; A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Mark (1921) Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark

Inge, W.R.; The Gate of Life (1935) Longmans, Green and Co: London

Jeremias, Joachim; The Parables of Jesus (1963) SCM Press: London

McNeile, Alan Hugh; The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1957) MacMillan: London

Mann, C.S.; Mark (1986) Doubleday: New York

Oesterley, W.O.E.; The Gospel Parables in the Light of their Jewish Background (1936) SPCK: London

Plummer, Alfred; A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Luke (19??) Edinburgh

Swete, Henry Barclay; The Parables of the Kingdom (1920) MacMillan: London

Swete, Henry Barclay; The Gospel according to St. Mark (1909) MacMillan: London

1 comment:

82%

Post a Comment